Some stories don’t shock you. They don’t scream. They don’t rely on dramatic twists or loud villains. Instead, they sit with you patiently, quietly reminding you of things you already know, but have learned to ignore.

Haq is that kind of film. I recently watched this movie on Netflix, directed by Suparn Varma. The title itself sets the tone for everything that follows. According to Wiki, Haq is an Arabic and Urdu word that means a right, a truth, something that is owed and not meant to be begged for. It is not a favour or an act of kindness. It is a moral and human entitlement. And that meaning is important, because this film is not about generosity. It is about what happens when someone has to fight for what should never have been negotiable in the first place.

At first glance, the story feels simple. A woman is abandoned by her husband after years of marriage. He remarries. He moves on with his life. She is left behind with responsibilities, children, and unanswered questions. When she asks for financial support — something that should be straightforward — she is met with resistance. Not just from her husband, but from the system itself.

But Haq is not really about marriage or divorce. It is about what happens when a person’s worth is reduced to what the law, culture, or tradition is willing to acknowledge.

Shazia’s story is painfully familiar, even if the details differ from person to person. She begins as someone many societies admire: loyal, committed, patient, and devoted. She believes in stability. She believes in sacrifice. She believes that doing the “right thing” will protect her in the long run.

Then life happens.

And suddenly, all that loyalty has no value in the spaces that matter most.

What makes Haq unsettling is how ordinary everything feels. There is no exaggerated cruelty. No dramatic violence. Just dismissal. Entitlement. A man who genuinely believes he has done nothing wrong because the rules have always favored him. A system that treats her request not as a right, but as an inconvenience.

That’s where the film becomes deeply relatable.

Many people know what it feels like to ask for something reasonable and be treated as though they are asking for too much. To be told, subtly or directly, that gratitude should replace justice. That endurance should replace fairness. That silence is more respectable than resistance.

In the film, Shazia is repeatedly forced to explain herself. Why she needs support. Why she deserves it. Why her suffering should be taken seriously. Each question chips away at her dignity, not because the questions are logical, but because they assume she must prove her humanity before it can be acknowledged.

And that’s the quiet cruelty Haq exposes.

Not the act of abandonment alone, but the exhaustion of constantly having to justify your existence.

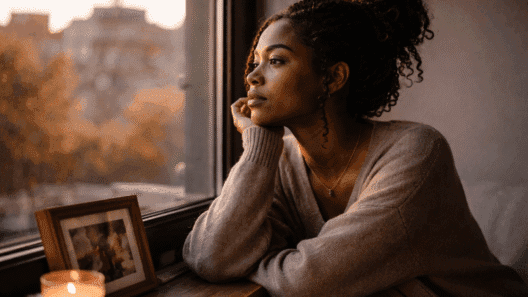

The courtroom scenes are especially powerful, not because of grand speeches, but because of their restraint. You can see it on Shazia’s face. The fatigue. The disbelief. The slow realization that this fight is not just about money or legality, but about whether her life will be recognized as valuable.

At some point in the film, it becomes clear that Shazia herself is changing. Not into a different person, but into a more awake one. She starts to understand that compliance has not protected her. That silence has not softened the system. That waiting patiently has only made it easier for others to move on without consequences.

That realization is uncomfortable because it mirrors what many people experience in real life.

There comes a moment when you understand that being “good” is not enough. That following the rules does not guarantee protection. That systems built without you in mind will not suddenly grow compassion just because you behaved well.

What Haq does beautifully is refuse to turn Shazia into a symbol instead of a person. She is not perfect. She is scared. She hesitates. She gets tired. She doubts herself. But she continues anyway. And that persistence, more than anything else, is what makes her story inspiring.

The husband, too, is portrayed in a way that feels disturbingly real. He is not a monster. He is not theatrical. He is simply comfortable. Comfortable in a world that excuses his choices. Comfortable knowing that tradition and interpretation will shield him. Comfortable believing that providing “something” is the same as doing right.

And perhaps that’s why his character feels so familiar.

Because injustice often survives not through evil, but through comfort. Through people who benefit from systems and see no reason to question them.

By the time the film reaches its later moments, Haq is no longer just about one woman’s legal battle. It becomes a reflection on how many lives are quietly shaped by laws, customs, and social expectations that were never designed to protect everyone equally.

It asks difficult questions without shouting them.

What does justice look like when the rules are uneven?

What does dignity mean when you have to fight to be seen?

And how much strength does it take to keep standing when the world keeps suggesting you should accept less?

The inspiration in Haq is not found in victory alone. It is found in refusal. Refusal to disappear. Refusal to be grateful for neglect. Refusal to accept that your pain is insignificant simply because acknowledging it would make others uncomfortable.

For OrangeCityz, this is the heart of the film.

Haq reminds us that growth sometimes begins when we stop negotiating our worth. That speaking up is not arrogance. That demanding fairness is not rebellion. That insisting on dignity is not a threat to society, but a necessary correction to it.

It is a film that stays with you because it doesn’t pretend the fight is easy. It simply shows that some fights are unavoidable if you want to remain whole.

And maybe that’s the quiet motivation it offers.

Not the promise of a perfect outcome, but the courage to say, “I deserve better,” even when your voice shakes.

Because sometimes, the most powerful thing a person can do is refuse to accept a life that keeps asking them to shrink.